Collecting & Conservation

“You cannot use what you do not have, so collecting the “missing” seed samples was a crucial early activity of the project,” notes Dr. Chris Cockel, who coordinated work on the Crop Wild Relatives (CWR) project at the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB).

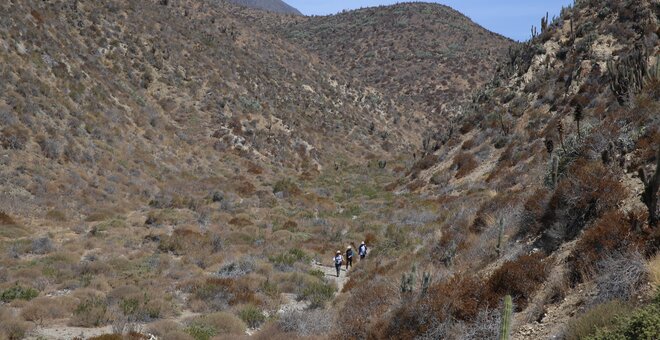

Starting in 2012, more than 100 scientists from 25 countries on four continents took part in a six-year quest to collect the wild plant species that scientists and breeders can use to make our crops more productive in increasingly challenging climates. After spending a collective 2,973 days in the field on exhausting and sometimes even dangerous expeditions, the researchers secured 4,587 unique seed samples of at least 321 crop wild relatives—many endangered—of 28 globally important crops. The largest number of wild relatives collected were those of potato, with 474 samples of 54 species, closely followed by eggplant with 438 samples of 33 species. The fewest wild relatives collected were those of chickpea, with 16 samples of three species.

A recent review indicates that this effort reduced the number of these crop wild relatives in urgent need of collecting from 185 to 108, with 61 of them now classified as needing no further collecting, meaning that their potential geographic distribution and distinct adaptations are probably well represented in genebanks today. Big changers include apple, Bambara groundnut and sorghum. Quite a turnaround from the situation in 2014.

By the end of 2021, 3,667 of the seed samples collected were deposited in the MSB, where they were dried, cleaned, tested for germination and checked to ensure they were properly identified before being entered in the MSB collection. (The others have not been sent to the MSB because they consisted of too few seeds, were diseased or for other reasons beyond the project’s control.) By mid-2021, some 3,279 accessions of 223 species had been sent to 10 international genebanks, where they have been planted out and seed stocks multiplied so that there is sufficient seed to conduct further trials and distribute to users on request.

For example, 1,462 accession were sent to the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) in Lebanon for multiplication, and by the end of 2021 some 800 of them had been successfully regenerated and seed of more than 500 of them had been sent to the ICARDA genebank in Morocco as a safety duplication and a similar number had been deposited in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

The MSB at Kew was instrumental in much of this work, providing hands-on training to 174 participants from the 25 national partners in seed collecting, cleaning and drying, and in making herbarium specimens, both at Kew and in partner countries. In addition, they provided country- and species-specific collection guides and equipment kits to facilitate processing of the seeds. The latter included everything needed for collecting, cleaning and drying seeds, packed neatly into large blue drums, which could be used in the field as well as back at their home institutions to dry seeds before they went for storage.

The guides (a kind of bespoke field guide to crop wild relatives) have all the information seed collectors need, including key features that distinguish the target species from closely related species in the region, plant phenology, habitat and altitude range, and suggested seed collecting methods to ensure high-quality collections. The guides also include predicted distribution maps and images of live plants and dried herbarium specimens.

Bringing together the national partners with experts at Kew built on the strengths of both.

“Our partners know their countries and they know about the flora of their countries. We know about seed physiology, about collecting seeds of wild plants. So joining forces in this experience benefits us all,”

Kate Gold, former Head of Conservation and Technology at the MSB

Building capacity

This process not only got the job done, in terms of collecting seed samples of the target species, but also strengthened national capacities for collecting, conserving and using such seeds in future. Contributing to this, the project also worked with 39 national genebanks to understand their information systems and needs. It has also helped 28 national and regional genebanks to improve their data management, including providing information technology equipment and assisting them in adopting GRIN-Global, a commonly used data management software in genebanks around the world. Some 140 people, half of them female, were trained in the use of these information systems.

Sharing the knowledge

But collecting the seeds alone is not sufficient, and the project has dedicated a lot of time and effort to capturing and sharing key data about the samples—including so-called passport data, which includes detailed information about the collection site, such as coordinates and altitude, as well as taxonomic identification. This information can point to seed samples that might be tolerant of, say, drought or salinity or that might be resistant to diseases or pests that are found where they were collected.

Passport data on the CWR collected is stored in Genesys, an online platform managed by the Crop Trust. By the end of 2021, data on 4,264 seed samples collected under the project were available on Genesys.

A solid foundation

This combination of collecting and conserving wild relatives, enhancing the technical and social capacity of the national partners and ensuring that vital information about the seed samples collected are freely available to users, such as researchers and breeders, provides a solid foundation for the use of these crop wild relatives to develop climate-change-resilient food production systems in the future.

Related information

- The story of the collecting phase of the project is told in full in A global rescue: Safeguarding the world’s crop wild relatives.

- Collecting guides

Top Collecting & Conservation Stories

Building Capacity in Collecting and Conserving Crop Wild Relatives

How do you go about finding and collecting seeds from a scraggly looking crop wild relative in a prairie or a tropical forest, when you’ve never done it before? Once you’ve collected them, how do you keep track of the seeds...

27 Jul 2020

27 Jul 2020

Wild Plants from Four Continents Deliver Climate Change Lifeline for Crops

Nearly 5,000 seed samples of crop wild relatives saved in challenging, six-year effort to secure the future of food

Bonn, Germany and Washington, DC (3 DECEMBER 2019)—As the world grapples with the challenge of sustainably...

2 Dec 2019

2 Dec 2019

Wild About Bananas

Hunting for Drought Tolerance in Papua New Guinea

Bananas were first domesticated in Southeast Asia, sometime between 5,000 and 8,000 BCE. They have since spread widely around the world. India alone consumes a quarter of the...

12 Nov 2019

Selected publications on Collecting & Conservation

- Adapting agriculture to climate change: A synopsis of coordinated national crop wild relative seed collecting programs across five continents Published: 2022

- Past and future use of wild relatives in crop breeding Published: 2017

- An inventory of crop wild relatives of the United States Published: 2013

- A prioritized crop wild relative inventory to help underpin global food security Published: 2013

- A case for crop wild relative preservation and use in potato Published: 2013