Gap Analysis

The Crop Wild Relatives (CWR) project did not just pitch straight in with collecting wild relatives of crops—instead, it started by carrying out the first major study of what crop wild relatives were already conserved in the world’s genebanks and where the gaps were.

“We knew there were gaps in the wild relatives in genebanks,” said Nora Castañeda-Álvarez, then a researcher at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and now with the Crop Trust. “The whole idea of the project was to collect representative crop wild relatives and conserve them in genebanks and then to use some of these in pre-breeding. But before we could do this, we needed to know what was missing from the ex situ collections. So that’s where we started.”

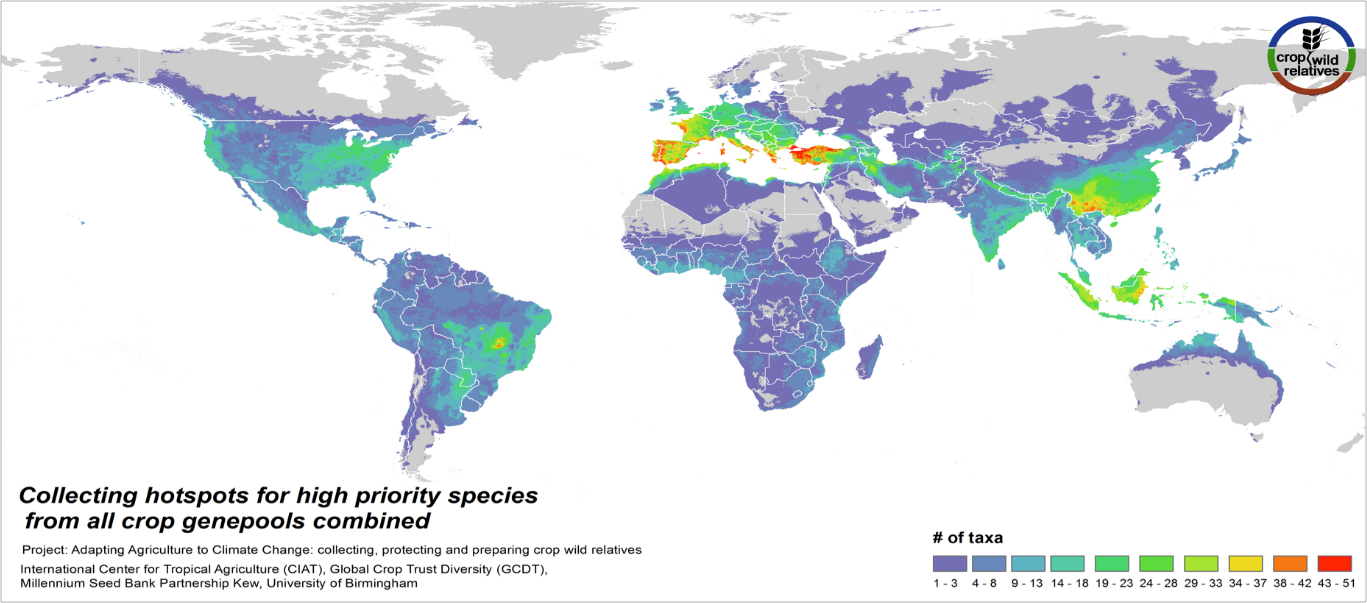

This study mapped 1,076 CWR of the world’s 81 most important crops and found significant gaps in the world’s genebanks, both in terms of species and regions.

Overall, nearly one third of the CWR included in the study were completely missing from the world’s genebanks and 70% were in urgent need of collection and conservation to ensure that they are not lost forever.

“Worldwide, there are dozens of genebanks safeguarding the diversity of food crops,” said Castañeda-Álvarez. “But many important species were entirely absent from these collections or were seriously underrepresented in them. We needed an urgent rescue mission to find and safeguard as many crop wild relatives as possible before they disappeared from their natural habitats.”

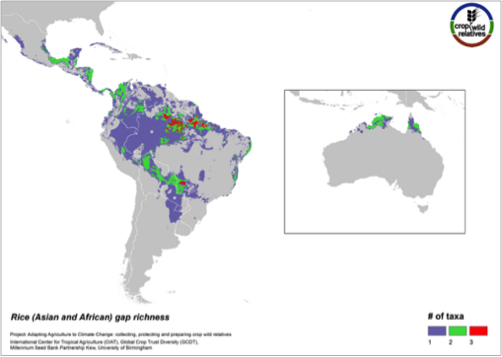

The study showed that wild relatives of crops important for food security like banana, cassava, sorghum and sweetpotato were in urgent need of collection, along with those of pineapple, carrot, spinach and many other fruits and vegetables. There were even significant gaps for the wild relatives of vital staples like rice, wheat, potato and maize—which tend to be better represented in genebanks.

“Our findings gave us the clearest idea yet of which plants were missing and where in the world we needed to search for them,” said Colin Khoury, a co-author of the study and a researcher at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and Director of Science and Conservation at the San Diego Botanic Garden, USA. “Some of the important collecting locations were a surprise—places that are not usually considered highly diverse. One of these was northern Australia, where there are wild relatives of sorghum, pigeonpea, rice and sweetpotato, although we did not collect there because the focus of our collecting efforts was on developing nations.”

Based on the analyses of these findings, combined with assessments by a global panel of 44 experts on crop wild relatives, the CWR project decided to focus on collecting, conserving and using the wild relatives of 29 crops. This formed the basis for the collecting phase of the project, identifying those species that most needed to be collected and where they were most likely to be found.

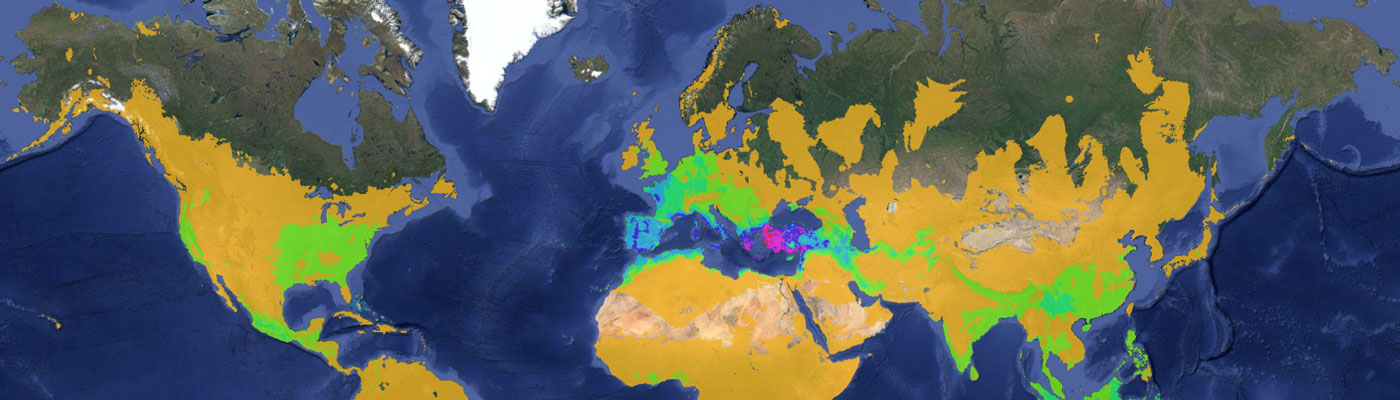

The gap analysis identified collecting priority hotspots at the species level, i.e. the number of high-priority CWR species that were in need of collecting in any particular area. Particularly important areas for collecting of these CWR include the Mediterranean and the Near East, Europe, East and Southeast Asia, the United States, the Andes and Brazil, northern Australia and West, East and Southern Africa.

“A large part of the decision on which of the 81 crops to choose was whether they were on the Annex 1 crops covered by the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture,” said Castañeda-Álvarez. “This means that it is much simpler to share the seeds among genebanks and with other users, such as breeders and researchers,” she noted.

The gap analysis also generated crop-level maps of areas where gaps in genebank collections were greatest, providing clear guidance for future collecting missions.

While the CWR project chose to focus on 29 crops, the results of the gap analysis are an invaluable resource for other national and regional efforts to prioritize and plan their own CWR conservation efforts, as illustrated by a recent study of Mesoamerican crop wild relatives led by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Resources developed

The resulting inventory of CWR, which provides a priority list of CWR species, along with key ancillary data such as their regional and national occurrence, seed storage behavior and herbaria housing major collections of CWR, is available through the US National Plant Germplasm System.

The occurrence data—information on the different CWR already in genebank collections, such as where they were collected from—are available on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF).

Highlights

Crop Wild Relative's Gap Analysis

Over 70% of essential crop wild relative species in urgent need of collection, says new research - a first of its kind, global mapping project reveals gaps in wild crop genetic diversity for agriculture to adapt to future climate...

21 Mar 2016

21 Mar 2016

‘Diversity Trees’ Shed Light on Gaps in Genebank Seed Collections

The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 2.5 calls on the world to maintain the genetic diversity of food. This includes cultivated plants, domesticated livestock and their related wild species.

The goal’s formal deadline...

13 Apr 2022

Top Publications on Gap Analysis

- Status of the Ex Situ and In Situ Conservation of Brazilian Crop Wild Relatives of Rice, Potato, Sweetpotato, and Finger Millet: Filling the Gaps of Germplasm Collections Published: 2021

- Filling the gaps in gene banks: Collecting, characterizing, and phenotyping wild banana relatives of Papua New Guinea Published: 2021

- Global conservation priorities for crop wild relatives Published: 2016

- Geographic analysis for supporting conservation strategies of crop wild relatives Published: 2016

- An approach for in situ gap analysis and conservation planning on a global scale Published: 2016